At Straight Up, we believe in the power of stories. But what makes a great story and why is storytelling so important? How can brands use storytelling to highlight the impact of their work and develop deeper relationships with their audiences?

We reached out to two people we admire greatly who are trailblazers and experts in the craft of storytelling. What follows is our conversation with Meg Griffiths and Scott Faris, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Meg and Scott are the co-founders of Universe Creative, a production company committed to social impact storytelling. They collaborate with foundations, nonprofits and socially conscious brands to highlight the impact of these organizations’ work through stories. Meg and Scott are documentarians, marketers, former educators and journalists – and they bring all of these skills to bear in telling the stories that educate and inspire, help us grapple with ambiguity, and emphasize our shared humanity.

You can learn more about Meg and Scott and their work at www.universecreative.org

We have been looking forward to talking with you today. Let’s start by talking about the company you co-founded, Universe Creative, which is focused on storytelling for good. What is the role of storytelling in social impact work?

Scott: At a very high level, stories make issues real. They make them relatable and visceral, and they create a sense of urgency. They create a sense of relatability because you can see yourself in the characters who face these daunting situations or you can see someone you know.

Our experience has been that even if you fully understand the contours of an issue, seeing or hearing or experiencing a story about someone who was going through that experience brings it to life in a way that just feels much more real and human than you would ever get from a fact sheet on an issue.

Meg: Ultimately, it’s about empathy. This is how we connect and understand each other. Empathy is one of the most human emotions, and so what we seek to do in our form of storytelling is to elicit empathy and understanding. People lean in when they hear a story and it makes them care.

Scott: There is also something evolutionary about storytelling, in that our brains are predisposed to cause and effect. Story is often a compelling way to arrange an issue or set of facts into a cause and effect structure that our brains are likely to soak up.

As film makers, how does the role of documentary film, specifically, help tell a story?

Scott: There’s often a moment when we’re shaping pieces that we are focused more on the emotional landscape of our characters, and I think that is sometimes missed in journalism because it feels a little too subjective. One of the privileges of the documentary is that we can really lean into the subjectivity of what we are doing. No documentary that we’ve ever produced purports to be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, which I think for some journalists feels frightening. For us, it feels liberating.

Meg: There is also storytelling focused on advocacy, and that plays a different role in the kind of story you tell. Are you telling a story from the perspective of really trying to get somebody on board with an issue? Or are you trying to get the truth of somebody’s experience? Are you telling it from a more objective point of view? These are the conversations that we’re always having, depending on the type of story that we are hoping to do and who we’re telling it in partnership with.

One of the lines from your website that struck a chord with us is “The universe is made of stories.” What’s the significance of that to you?

Scott: “The universe is made of stories” comes from a Muriel Rukeyser poem. The idea is that there is a set of scientific claims that can be used to explain human consciousness and the world that we live in, but it’s not nearly as compelling as the cause and effect framework that a story provides. And that suggests what makes a good story good, which is that there is a kind of logical sequence of cause and effect. There are characters that you may see yourself in sometimes, and other times not, but either way, stories represent something that feels authentic to the human experience.

We also believe that a compelling story entails some sort of up and down, some sort of dynamic. It’s an important part of storytelling to see some moment of struggle. Where’s the tension in the story? This is not about brands taking advantage of situations to position themselves as saviors. It is really about highlighting personal struggle and tension to reconcile some kind of meaning.

Is there a formula to good storytelling?

Meg: There is not a formula. There are the best practices of storytelling, such as having an arc and a three act structure, and we definitely bring those storytelling principles to bear, but I really don’t think there is a formula beyond just listening and being on the lookout.

We’re constantly trying to populate our world with the kind of stories that excite us. There is always a moment on a project when you hit on “the thing” that is fascinating and you want to know more. The visuals start to pop into your head and you get goosebumps – and you know that is the story.

Compelling storytelling, in its simplest form, is when you show a story to someone and they respond to it. This tells you that you’re not alone as a human being – this is inherently a community building act.

Earlier you said this is not about brands positioning themselves as saviors. What challenges do you encounter when working with socially conscious brands to tell authentic stories?

Scott: It can be challenging from a client’s perspective because they are already going out on a limb to attach their brand to a narrative, which feels like a risk. They want an impact story. They want a personal narrative. And then the client sees what you’ve made and they start to backtrack because they get nervous. They want to make that story “safer” in all sorts of ways that can hurt its authenticity and, frankly, its appeal. We always ask, “Would you want to watch this? Would you share it with your partner or a friend?” I think our capacity to delude ourselves is great, especially when we have a vested interest in the brand that’s being represented in a piece of content. Sometimes it takes some work to hold the client’s hand through honestly answering this question.

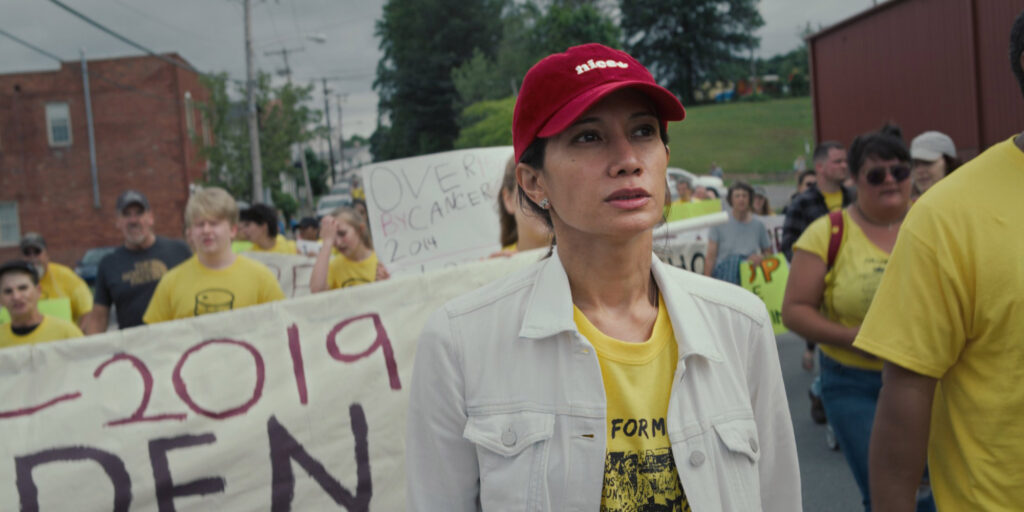

Meg: In the documentary we co-produced, Impossible Town, the ending isn’t what you expect and it leaves you with questions. I think that this is part of our job as storytellers – to generate dialogue and to help people ask questions and grapple with content that isn’t always easy to watch or understand.

We hope that a story inspires conversations or makes someone think differently about the topic, but we do go back and forth over whether that is our primary measure of success.

Have you ever been surprised with the direction a story takes?

Meg: In the process of making Impossible Town, there were three distinct moments in the making of the film when we reflected that this story is not what we thought. That story really forced us to make some difficult choices and have hard discussions. But the product is better for it.

Scott: There are also plenty of examples when we’ve been in the middle of client work and engaged to tell the story of a subject. In the process of telling that story, we realized that this person’s life doesn’t neatly align with the message the brand is trying to convey. Unfortunately, in those cases, the story of the subject is sometimes flattened or obfuscated to serve the brand. And that feels terrible.

As marketers we know that storytelling is essential to creating a strong brand and building connections with customers, but often the best efforts are compromised by internal agendas. So what separates marketing storytelling from pure storytelling, or is there a difference?

Scott: If I had to name one thing, it’s “Do you feel the brand imposing on the authenticity of the story being told? We’ve done enough stories when that is true to know that it does not feel good. And those stories typically do not yield impressive results.

Meg: The brands right now that are doing really true, interesting branded content are partnering with filmmakers to take that risk. It’s exciting. If brands can allocate some of their marketing budget towards really going out on a limb, there is such a great storytelling potential there. It doesn’t have to be documentary – there are many other forms of storytelling that allow you to really watch what unfolds.

Brands are going to increasingly have to step into that space. There may be some interesting solutions where brands, streamers and filmmakers come together to ensure that these stories get made.

Is there advice you would give an organization struggling to tell their purpose?

Meg: It is really helpful for an organization to have done a branding exercise before stepping into a storytelling engagement: Having a sense of who the brand is, who they’re trying to talk to, what they’re trying to achieve with a piece of content. The video cannot do everything. You have to see it as a piece of content within a larger ecosystem.

Do you know who you are as a brand? What will a video specifically do for you? Once you’ve drilled into that, creative heavy lifting can happen because it is a frame for the story. The process of clarification is really important.

How did you decide what story to tell in your first documentary film, Impossible Town?

Scott: Very early on we realized that when we have the opportunity to do narrative work in places that feel like home to either one of us, the work feels that much more personally fulfilling and engaging. I grew up in West Virginia, where the story takes place, and my family comes from West Virginia. This is a place I have been invested in as a storyteller.

There is no philanthropic money being spent there, so if we wanted to engage in some project there we had to find a story that we felt was compelling. We met our protagonist, Dr. Amjad, and we felt for the first time that the story we were telling was truly a process of discovery. As we were capturing the story, our understanding of it was evolving. And that is so rare when you’re doing client-driven work. There’s just too much on the line to open yourself up fully to the process of discovery because there’s always a possibility that things could collapse like a house of cards.

Impossible Town doesn’t necessarily have the ending we may have expected or hoped for, and that makes us wonder, how do you keep your spirits up when you come across difficult stories?

Scott: There is an inherent beauty in framing those stories of sadness through the storytelling devices that we often use to bring our pieces to life. There’s an opportunity to give a story context and, in the best case scenario, to help someone who has been afflicted by something unfortunate but empowered by what they have survived. When you’re able to take something sad and create a point of inflection for both the person involved and for those watching the story, then it becomes something quite beautiful.

Meg: Some of the real highlights of our collaboration have been when we’ve been able to watch the work we’ve made with the people we made them with. We recently held a small private screening with a group of people who had experienced a trauma, and to see their story reflected, well, the feeling in that room and the ripple effect of the story and the conversations after were very powerful. I’m certain when I’m old and look back on my life, those will be the moments that I remember. For people to see themselves on a big screen and to feel that their story is that big, there’s nothing that really replaces that feeling.

Many would argue that connecting with our shared humanity is more urgent than ever in our society. In today’s fraught climate, do you think it’s possible to tell authentic stories that don’t trigger some kind of political stance?

Scott: In Impossible Town, we made the conscious choice to omit politics from the story because we did not want viewers to be distracted. There’s a kind of beauty in the ambiguity.

Meg: And the issues reflected in the film are not political – they are humanitarian. We are able to process a lot of the divisiveness in society by putting ourselves into parts of the country that may look different than where we are from. This allows us to have conversations and deepen our own understanding, which is important to the work we do because we’re not bringing a fixed lens on it.

What’s next for you both?

Scott: Our work with nonprofits and foundations will always play a role in the identity and longevity of our business. It is work we find extremely fulfilling. On the other side of things, we would love to continue to lean into documentary storytelling that can reawaken our appetite for dealing with topics that feel ambiguous or uncertain, about which there are no easy conclusions to draw. As a society we’ve sort of lost our ability to sit in ambiguity and withhold moral judgment on issues that feel complex because it is more satisfying to immediately know what is right and what is wrong. But this mindset will propel us down a path that is fraught with danger. Really daring documentary storytelling has the ability to reawaken our appetite for curiosity and tolerance, and a withholding of moral judgment.

“Really daring documentary storytelling has the ability to reawaken our appetite for curiosity and tolerance, and a withholding of moral judgment.”

We hope that we’re lucky enough to be involved in storytelling that moves the needle on that, and that we’ll be part of a wide collective of folks who are after the same goal, because this isn’t the responsibility of any single individual or individual storytelling team.

Meg: This work is ultimately about empathy, and as we think more about the stories we want to tell, we want to sit in that gray area with someone who might not think you share anything in common but realizes that there are ways in which we can relate to each other. We hope the stories we tell help to create those bridges, and we definitely see more space for brands to step into that idea full-heartedly.